Jesus prayed to his father in heaven, for his disciples: ‘that they may be one, as we are one.’

A sermon preached by Canon, Edward Probert, Chancellor on Sunday after Ascension, 21st May 2023

(Acts 1.6-14; John 17.1-11)

Jesus prayed to his father in heaven, for his disciples: ‘that they may be one, as we are one.’

* * * * *

You may have worked out from the music in today’s services that we are honouring the composer William Byrd, who died in 1623, 400 years ago; he had lived all of 80 years.

Byrd had the blessing, or curse, of living through what might be called ‘interesting times’. On the positive side, he was born before William Shakespeare, and died after him; this was an exciting period culturally.

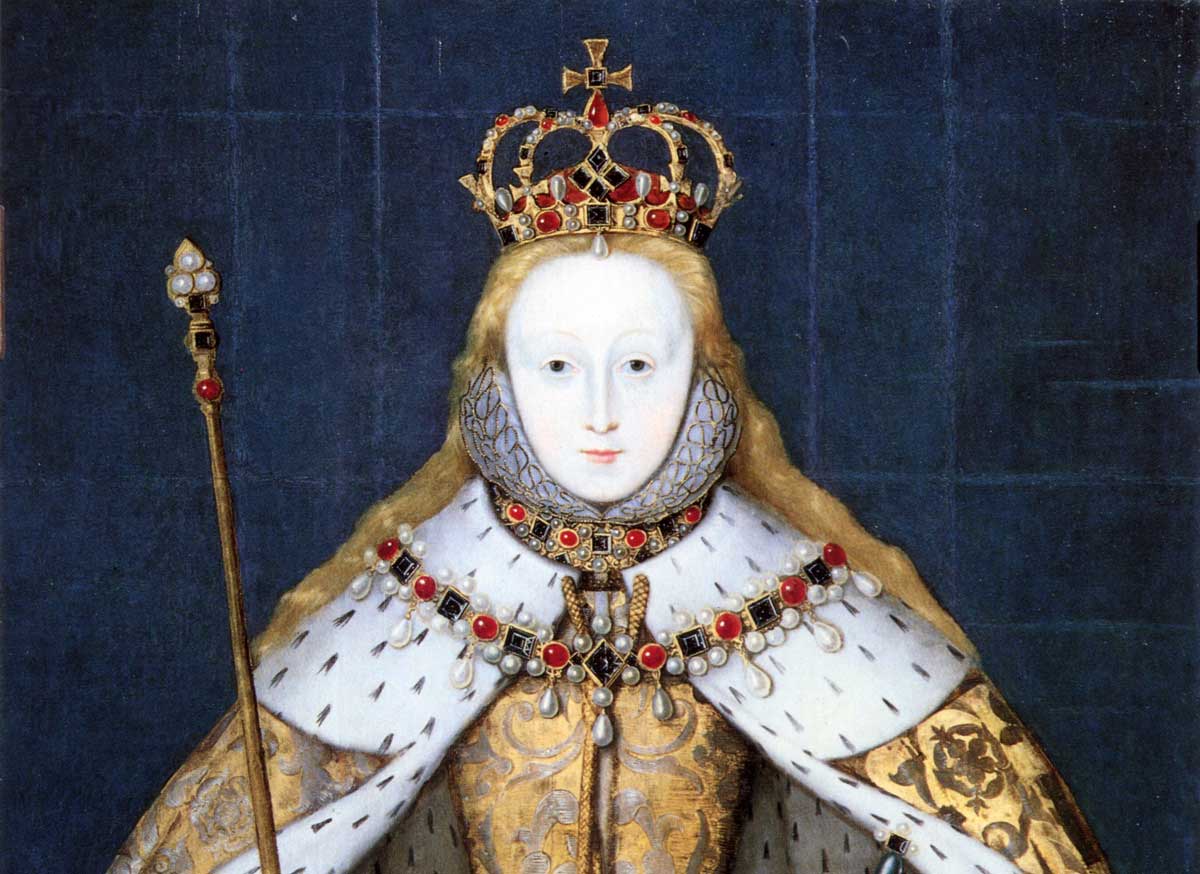

Now Byrd was a lifelong Roman Catholic. He was born during the reign of Henry VIII, who had cut the English Church off from Rome; and whose successor Edward led the Church into Protestant and English patterns of belief and worship. Then, when Byrd was 10, it was all change: the staunchly Roman Catholic Mary on the throne, the reinstatement of the Pope and the Catholic hierarchy, the return to Latin worship, the execution for heresy of the former Archbishop of Canterbury and other Protestants, including some here in Salisbury. When Byrd was 16, in came Queen Elizabeth, whose unusually long reign at least provided some stability, but whose policy towards Roman Catholicism became harsher in the face of excommunication by the Pope, attempted invasion by King Philip of Spain – who had formerly been her brother-in-law, and King Consort of England – and in Elizabeth’s last years Roman Catholic priests were treated as traitors, agents of a foreign power. In his final 20 years, James Stuart of Scotland was king of England in a reign indelibly marked by the attempt of a Catholic plot to blow up King and Parliament.

For much of his life William Byrd worked for these various Protestant monarchs. He was a chorister and later organist in the Chapel Royal, organist at Lincoln Cathedral, and held with Thomas Tallis a monopoly to publish music granted by Queen Elizabeth, to whom these two Roman Catholic musicians loyally dedicated their first publication. Meanwhile Byrd also composed music for Roman Catholic worship, including the Latin texts used in this service.

For many, these 80 years which Byrd spanned were bitter, and binary – you worshipped either in English or Latin, you were a Catholic or Protestant, you stuck with the Church of England or you were a traitor. But here was a man who lived – honourably – with two loyalties, and who did not succumb to that binary choice, either/or. So he stands not only as a fine composer, but to remind us that truth can be complex, and that hard and fast boundaries and single loyalties can bring harm not good.

We’re in the period between Ascension Day and Pentecost – suspended, you might say, between earth and heaven, between the earthly Christ and the coming Holy Spirit. In Acts, the question put to the disciples as they parted with Christ was: ‘Why do you stand looking up towards heaven?’ Apparently they gave no answer; but they might have said that heaven, where Jesus was, was the place where their sights were set. Instead of that heavenly gazing, they were sent off to worship and pray, and to wait to experience the disruptive power of the Holy Spirit. For us earthly disciples of Christ, the simple, beautiful contemplation of eternal life with God is always paired with the challenge to live now, in this untidy, complex and often cruel world: a world needing the work of organisations like Christian Aid, as well as the beauties of music such as Byrd’s.

We are creatures of earth and heaven, and we are called to live in both: as Jesus did (and as he still does, in bread and wine); and as does the Holy Spirit of God, comforting, encouraging, disturbing, empowering. Two loyalties, which cannot be divided. Jesus prayed that we might be one, as he and his father are one.