A Sermon for The William Byrd Festival

A Sermon preached by the Precentor, Canon Anna Macham, at Choral Evensong

Sunday 21 May 2023 16:00 The Seventh Sunday of Easter

2 Samuel 23: 1-5 and Ephesians 1: 15-end

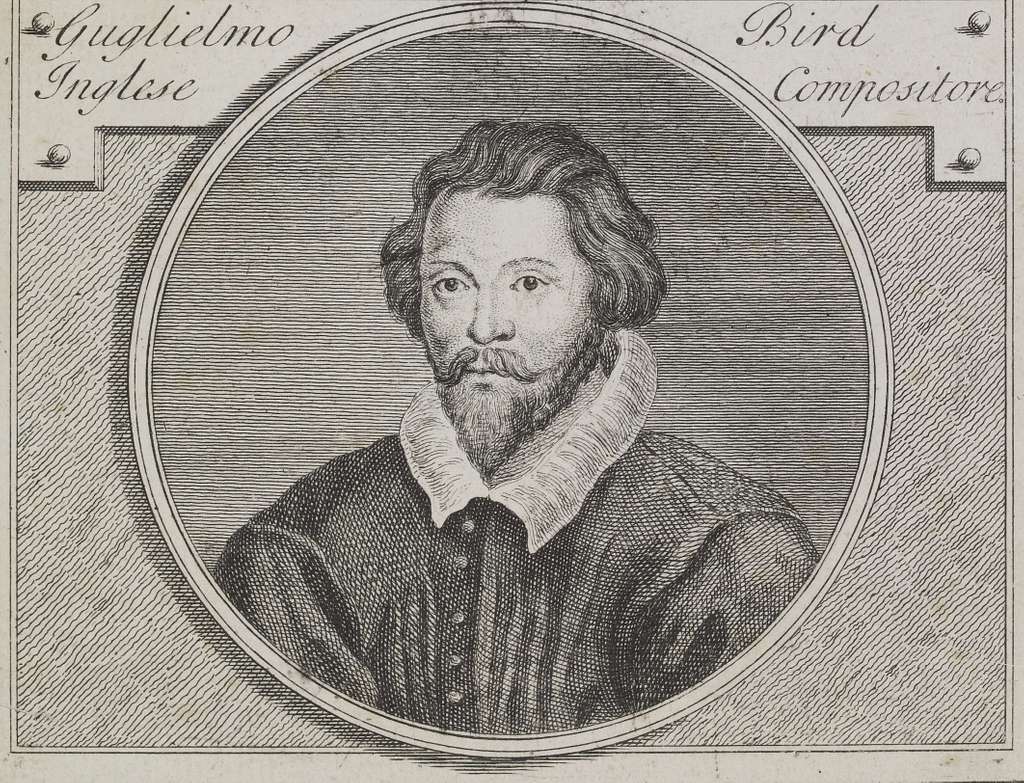

Our service of Evensong this afternoon marks the end of our William Byrd Festival. Throughout the weekend, we’ve been treated to a wide range of works from this prolific late Renaissance composer, who lived to the age of over 80 and died 400 years ago this year- from the Compline hymn, Christe qui lux es et dies sung by our Lay Vicars at Compline on Friday evening, to the energetic and bold Fantasia in A minor, our organ voluntary last night, to the Mass for Five Voices in our Eucharist this morning. The concert of songs accompanied by lute this afternoon alerted us to the fact that- far from only composing English sacred music and Latin masses and motets – Byrd wrote in almost every genre of his day. This included accompanied and unaccompanied secular songs, and a wide variety of music for keyboard and strings.

For Byrd to set the mass to music in the 1590s, which is when he wrote his 3 settings of the Latin mass for 3, 4 and 5 voices, was a hugely risky thing to do. Though he thrived in a newly Protestant nation, acting as a revered court composer in public, in private – as a Catholic dissident – he composed music for secret Catholic services. 1540, the year of his birth, was the year in which Henry VIII finished dismantling the monasteries and convents, brining about the English Reformation. Far from the ideal of a king ruling over people justly held up in our first reading, from 2 Samuel, Henry was a capricious tyrant, and persecution of Catholics intensified under Elizabeth I in the 1580s. The celebration of the old Catholic liturgy in England was strictly banned, and those who went on cultivating it could be punished with fines, imprisonment, or, in exceptional cases, even death. What had taken place daily at every pre-Reformation altar, from the humblest parish church to the greatest cathedral, was now a rare and dangerous luxury.

As they were performed in secret, not publicly in churches, not much is known of how Byrd’s mass settings were put to practical use. The music was probably sung by small groups rather than large choirs, in Catholic households or domestic chapels. Interestingly, some of these clandestine household choirs seem to have been of mixed gender, reflecting the important role played by women in Elizabethan domestic music-making. An account of a week-long musical gathering held in 1586 of Catholic Jesuit singers- an event at which Byrd himself was present- refers matter-of-factly to “singers, male and female” (see Kerry McCarthy, Byrd, OUP, 2013, p.149).

The anthem we’ve just heard sung by our choir, the double motet Ne irascaris, Domine, was composed earlier than the masses, in 1581, but still in this period of intense persecution of Catholics and was published in 1589. Like the Latin mass, Latin-texted motets like this one were not performed in church, but they were widely tolerated and loved as chamber music, again in private settings. They were performed by educated Elizabethans and circulated among skilled musicians of all sorts: Catholic and Protestant, male and female, courtly and bourgeois. Most of Byrd’s motets from this period of his middle age are anguished confessions of sin, pleas for rescue from tribulation, or laments over the fall of an allegorical “Jerusalem” or “holy city.” It seems highly likely that many of them were inspired by Byrd’s distress at the increasingly dire predicament of the English Catholic community.

We can hear Byrd’s sense of weariness and desolation in Ne irascaris. Although the piece starts in a major key, the major chords here create a grave effect. The text is from Isaiah (64:9-10), concerning the exile of the Israelites from their city, Jerusalem, It begins with the exiles’ plea: “Be not angry, O Lord.” “Now consider,” it continues, “we are all your people. Your holy cities have become a wilderness…Jerusalem a desolation.” The mood from the start is solemn and sombre. Its long, brooding conclusion brings into focus the final cry that Jerusalem is desolate, finally ebbing out with some flat sevenths in the alto in, as one critic puts it, “an audible image of weariness and desolation” (McCarthy, p.109).

This piece reflects Byrd’s own distress, or that of his people, a persecuted minority, but it’s also timeless. Listening to it today, it might make us think of other, more recent periods of oppression, persecution and destruction. Last Sunday was Ukrainian Mothers’ Day; in a Facebook appeal marking the day, the Primate of Ukraine’s independent Orthodox Church (OCU), Metropolitan Epiphany (Dumenko), said that hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian mothers have been “forcibly separated from their children, awaiting them from the Front, and from occupation and captivity” (Church Times, 19 May 2023).

To listen to the music of grief and lamentation gives us hope, that our lament- and that of others- will be heard by God. In a busy world, where the language of lament is often forgotten or suppressed, beautiful, deeply skilled music like Byrd’s makes us stop and remember the desolate cities of our own time. It makes us face up to the forces of death that threaten to destroy us and our fellow human beings.

We tend to think of the Elizabethan era as a golden age of church music, but the reality was also that it was a very difficult time for musicians, and not only for Byrd. Although Elizabeth I’s restrictions on sacred music allowed for cathedral and collegiate choirs to be maintained, this was often disregarded or overlooked in favour of more pragmatic or puritanical views. The supply of qualified musicians was dangerously short at times. Many singers had to live on fixed stipends that had not been raised, despite rampant inflation, since the time of Henry VIII. One anonymous observer lamented that “whereas in former times of popery divers benefactions have been given to singing-men… the same is swallowed up by the deans and canons”; a contemporary singer’s salary, he said, “doth not answer the wages and entertainment that any of them giveth to his horse-keeper” (McCarthy, p.23).

As in our own day, music was not always valued- or funded- as it should be; to earn a living, musicians like Byrd had to look outside their own immediate milieu of the Church and work hard to persuade the wider world of the Elizabethan public- the ambitious middle classes and their families- to support music and engage with it, both financially and participation, persuading them of the benefits of a good musical upbringing and education for their children.

Byrd sounds curiously modern when, at the start of one of his song books, he lists for their benefit eight reasons, including non-musical ones, why he thinks that everyone ought to learn to sing. Singing is good for your health, he reasons; it strengthens the body “and doth open the pipes;” it leads to success in public speaking. Above all, he concludes, its beauty inspires us and lifts our spirits up to God in worship. “The better the voice is,” he writes, “the meeter it is to honor and serve God therewith: and the voice of man is chiefly to be employed to that end” (Byrd, Psalms, Sonnets and Songs, 1588, quoted in McCarthy, p.85).